|

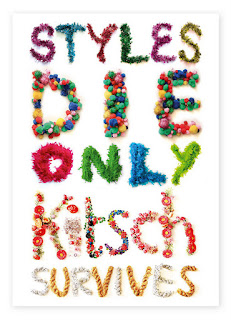

| 'Pensee' by Susan Waitt, presented to Le Salon at its inauguration |

Dust is what connects the dreams of yesteryear with the touch of nowadays. It is the aftermath of the collapse of illusions, a powdery cloud that rises abruptly and then begins falling on things, gently covering their bright, polished surfaces. Dust is like a soft carpet of snow that gradually coats the city, quieting its noise until we feel like we are inside a snow globe, the urban exterior transmuted into a magical interior where all time is suspended and space contained. Dust makes the outside inside by calling attention to the surface of things, a surface formerly deemed untouchable or simply ignored as a conduit to what was considered real: that essence which supposedly lies inside people and things, waiting to be discovered. Dust turns things inside out by exposing their bodies as more than mere shells or carriers, for only after dust settles on an object do we begin to long for its lost splendor, realizing how much of this forgotten object's beauty lay in the more external, concrete aspect of its existence, rather than in its hidden, attributed meaning.

Dust brings a little of the world into the enclosed quarters of objects. Belonging to the outside, the exterior, the street, dust constantly creeps into the sacred arena of private spaces as a reminder that there are no impermeable boundaries between life and death. It is a transparent veil that seduces with the promise of what lies behind it, which is never as good as the titillating offer. Dust makes palpable the elusive passing of time, the infinite pulverized particles that constitute its volatile matter catching their prey in a surprise embrace whose clingy hands, like an invisible net, leave no other mark than a delicate sheen of faint glitter. As it sticks to our fingertips, dust propels a vague state of retrospection, carrying us on its supple wings. A messenger of death, dust is the signature of lost time.From:

'The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury Of The Kitsch Experience'. Rather than engaging the tired stances that see kitsch as either bad taste or a bad copy of «true art», this book presents it as a cultural sensibility of loss, tracing its origins as a massive phenomenon to the nineteenth century. Presenting kitsch as the ambivalent «cristallization» of the lost experience of pre-industrial life, TAK explores this sensibility through the objects and narratives that it produced, in particular those related to the popular underwater imagery of the time: aquariums, paperweights, the myth of Atlantis and Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

No comments:

Post a Comment